Nutrient Relocation By Brandon Mitchell

One of the big problems we have in pastures as opposed to hay fields isn’t as much nutrient removal, but nutrient relocation.

One of the most common ways pasture nutrients are relocated is through set stocking, also called continuous grazing. Cattle, and other livestock graze across the field, then go to the edges where there is water or shade. With a fenceline border, the field edge receives more nutrients than it gives out and this is at the expense of other parts of the pasture.

When you drive around and see pastures with cattle, pay attention to the grass and not just the cows. If you do, you may notice the difference in color, growth rates, or forage types of the grasses within the pasture.

Here in my neck of the woods, broomsedge sage grass is prevalent when fertility is low, pH is low, or when stocking rate is too low or when using set stocking. Typically, two or more of these effects are going on simultaneously. When fall hits, this is particularly obvious due to the brown color of the dormant broomsedge in the fields. Usually, the brown areas that have the highest concentration of broomsedge are in the middle of the field while the outside ring is green. The size of the outer ring varies, but I simply call it the 80/20 rule.

About 80 percent of the pasture is losing nutrients, while the remaining ring around the edge is gaining nutrients. This exchange of nutrients eventually causes a problem with limited growth in the middle, while the edges receive excessive levels of nutrients that are wasted in one way or another. Either the nutrients are taken up by trees or brush, or the nutrients are washed out of the field by rain. Even when the edge is elevated where nutrients go back into the field, the imbalance is still problematic. And while many solutions may exist to fixing this imbalance, the simplest fix is usually more fence.

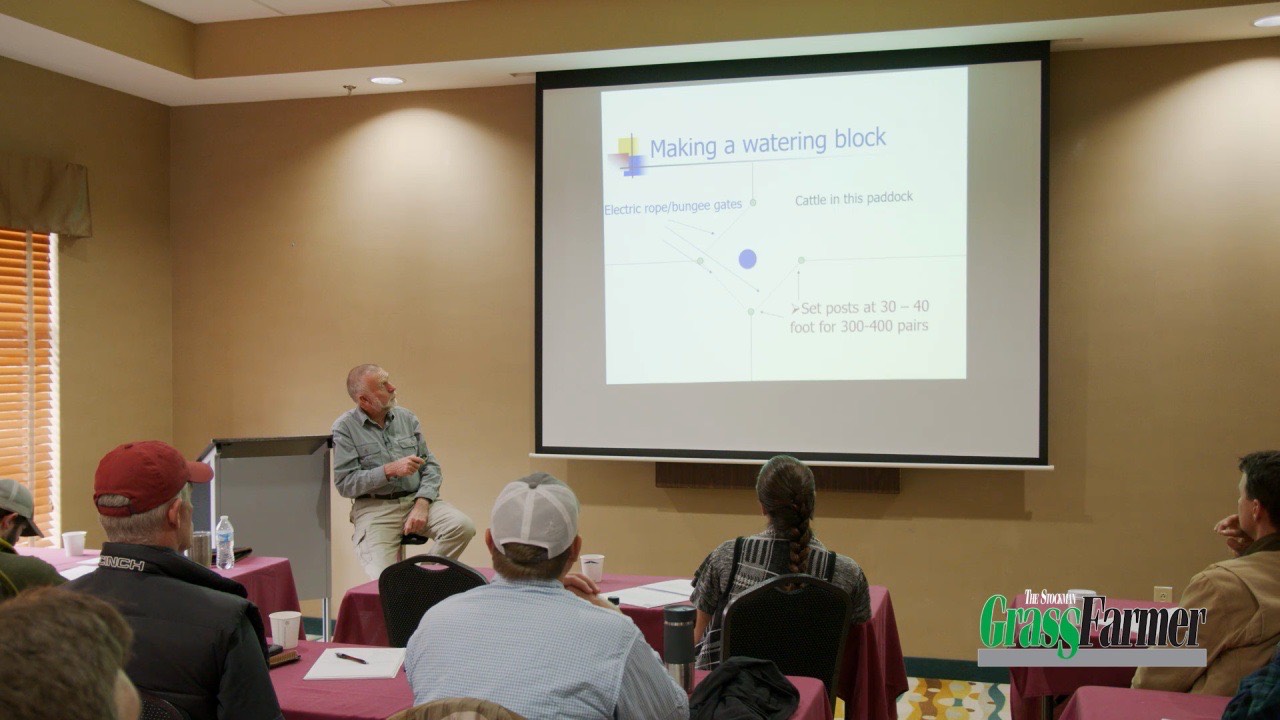

Portable electric fence is easily one of the best management tools we have. Not only does it keep cattle off sections of pasture to enable unhampered plant regrowth, but it also creates a barrier. It stops livestock from going into areas we don’t want, and it can create areas of higher livestock concentration. This changes the location of nutrient deposition.

In fact, I have found barriers like fences to be so effective in creating areas of higher nutrient deposition that I have theorized if one was to build a square fence in the middle of the field, it wouldn’t be long before you would see cattle trails surrounding the fence and higher soil fertility than in other areas of the pasture. And this is without the benefits of shade, shelter, water, or feed.

The fence we use to subdivide the pasture can be permanent or temporary fence, which is determined by the size and layout of the field. However, if the electric fence is permanent, you will not see all of the same benefits of nutrient relocation as you would with temporary fences that change location from time to time. Along with cross fencing pastures, one of the ways we relocate nutrients is with movement of feed and water resources. By placing hay, water, and minerals in different locations, livestock must travel around rather than lounging in one area. Water movement may not be easy, or even possible in some situations, but movement of minerals and hay often is. I’ve heard it recommended to place the water and minerals at opposite corners, and that is a good first suggestion, but if we can move the minerals occasionally to other areas, that is even better.

Barns and other permanent shelters are areas that nutrients concentrate when livestock have constant access. Sure, barns are great for lots of things, but they have drawbacks. If the barn is the only shade around, consider creating some other type of shade at other locations.

I’m a big fan of silvopasture, which combines trees and pasture. This spreads out the shade, and positions it throughout the field rather than just at the edge. However, it’s not the only option. There are lots of portable shade options for purchase, but you can also make your own. Heat tolerant genetics also play a part in how often cows spend in a barn (or pond for that matter).

Another way we can change nutrient relocation is with proper placement of hay. Not only does uneaten hay break down and become nutrients for the soil, but it also draws in livestock to specific locations. Livestock eat and loaf around the bales, depositing manure and urine. If we place our bales where nutrients are lowest, we see the most gain.

Additionally, when placing bales on high spots near the middle, any nutrients that runoff due to rain stay on the property. Bales placed near the edge of the property, especially in valleys (even small ones) means the nutrients wash out with rains.

For example, last winter I drove by a farm and saw where hay bales were continuously placed at low spots near the creek. It became muddy and cows and calves had to wade through the cold mud to eat. The ground was damaged by the compaction, and a lot of the nutrients left the field via the stream. It was a bad situation all the way around. But it wasn’t surprising that this management decision was poor. Only a few years before, I saw a newborn calf that had just been born in the field. It was just after Christmas, and it was sleeting. I often wonder if that calf made it. Management really is the biggest factor in the success or failure of our farms.

The last bit of advice I can give is to put nutrients back where they are needed. I’m not sure if mowing or cutting hay is to blame, but we seem to want to fertilize our fields in a pattern, placing nutrients evenly across the fields regardless of where they are needed. I’m not necessarily suggesting we should start grid sampling like grain farmers, but we should be trying to apply more nutrients towards the middle, on high and dry spots, and anywhere else that appears nutrient deficient (either by visual differences or soil test). We should also be careful of applications of compost, manure, or commercial fertilizer anywhere runoff is possible, especially when that runoff could go into a body of water or leave the property.

Nutrients don’t always leave the field they are on. Sometimes they are just moved around. It’s our job to put them back where they were. In a nutshell, it’s best to create portable fencing infrastructure to avoid areas of excessive nutrient deposition, manipulate water, minerals, and hay to concentrate nutrients where we want them, avoid excessive nutrients deposited around the barn by having multiple shade options, and avoid fertilizing near water sources, or where nutrients can easily run off property. If nutrients are relocated rather than removed, there are ways to put them back where they belong.

Brandon Mitchell has worked as an extension agent, and now an agricultural teacher.

Stay connected with news and updates!

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from our team.

Don't worry, your information will not be shared.

We hate SPAM. We will never sell your information, for any reason.