Keys to Success By Joel Salatin

From the monthly column Meadow Talk

I received a phone call recently from a consulting firm advising a $2 billion New Zealand agriculture cooperative (15,000 members) on how to move from commodity to craft. That’s a tall order on its face, but what was most interesting to me (I think I always learn more from these calls than they could possibly learn from me) is that the rancher/ farmer members are evenly divided between optimistic and pessimistic. In other words, the company wants to enter the green, no-chemical market and the producer members are at odds about whether it’s doable. Some are struggling and others aren’t. Some think they can make a transition to non-chemical without too much problem; others think it would be impossible.

That got me to thinking about some of Allan Nation’s (founder of Stockman Grass Farmer) countless gems shared with me over many years. I’m hoping you old subscribers will feel a bit like I’m channeling Allan here. You new ones who didn’t have the privilege of knowing Allan just realize I can’t begin to do him justice, but hopefully it’ll be good just the same.

What makes one outfit prosper and the other struggle? I’ll put my own alliteration on Allan’s answer to that question.

- Pretties. Allan’s axiom: “Profitable farms have a threadbare look.”

To be sure, Allan enjoyed beauty as much as anyone, but it wasn’t about the tractors, buildings, and fences; he looked at forage, animals, and faces. Too many farmers and ranchers spend too much time reading Southern Living. It’s a beautiful mag- azine, but all those pretty places take a lot of capital and maintenance. Allan’s family ran cattle on cane breaks in Mississippi’s lowlands, where weather, ground conditions, and cattle combined like a big salvage operation. Salvage operations can’t afford to be flashy.

White board fences make pretty covers on magazines, but they take too much time and money to be good investments on a farm. If you want to see threadbare farms, go to New Zealand. Two New Zealand farmer brothers stopped at our house one fall. They had 3,000 ewes that they left behind during lambing. “We leave for a month during lambing to keep us from building a lambing shed. When we get home, we enjoy the survivors and the dead ones have already been cleaned up by buzzards.”

That, folks, is a threadbare farm. They were upbeat and profitable. Kit Pharo guarantees his bulls haven’t had a calf pulled in their ancestral line back several generations. When asked how he births thousands of calves without assistance, he quips something like “When you quit help- ing, the ones that need it cull themselves.” That’s threadbare. My side-by-side is a 1987 Ford Bronco with all the back windows knocked out. Bought it for $1,800, has a windshield and roof, and seating for five people. All this thanks to Steve Kenyon’s advice, another threadbare afficionado.

- Peers. Allan’s axiom: “If your neighbor thinks your idea is a good one, don’t do it. If he thinks it’s the craziest thing he’s ever heard, you’re probably on the right track.”

Farmers tend to be overly clannish, probably because most are loners in society and feel culturally marginalized.

Tribalism runs deep in farming communities. Nobody wants to be the one with Johnsongrass and thistles when the neighbors are bushhogging. I remember an early column from our own grass guru, Jim Gerrish, where he itemized the things grass farmers like versus the things other farmers like. One was we love Johnsongrass and most farmers would rather go bankrupt buying herbicide to kill it than have one sprig show up in their fields.

Dave Pratt in his Ranching for Profit Schools hammered home the idea that average isn’t very good in the livestock business. If you want to thrive, you need to look at what the top 10 percent are doing, not the average. It’s easy to be average; that’s what everyone else is doing. If you want to be on the enthusiastic end of farming, you need to do the unorthodox thing.

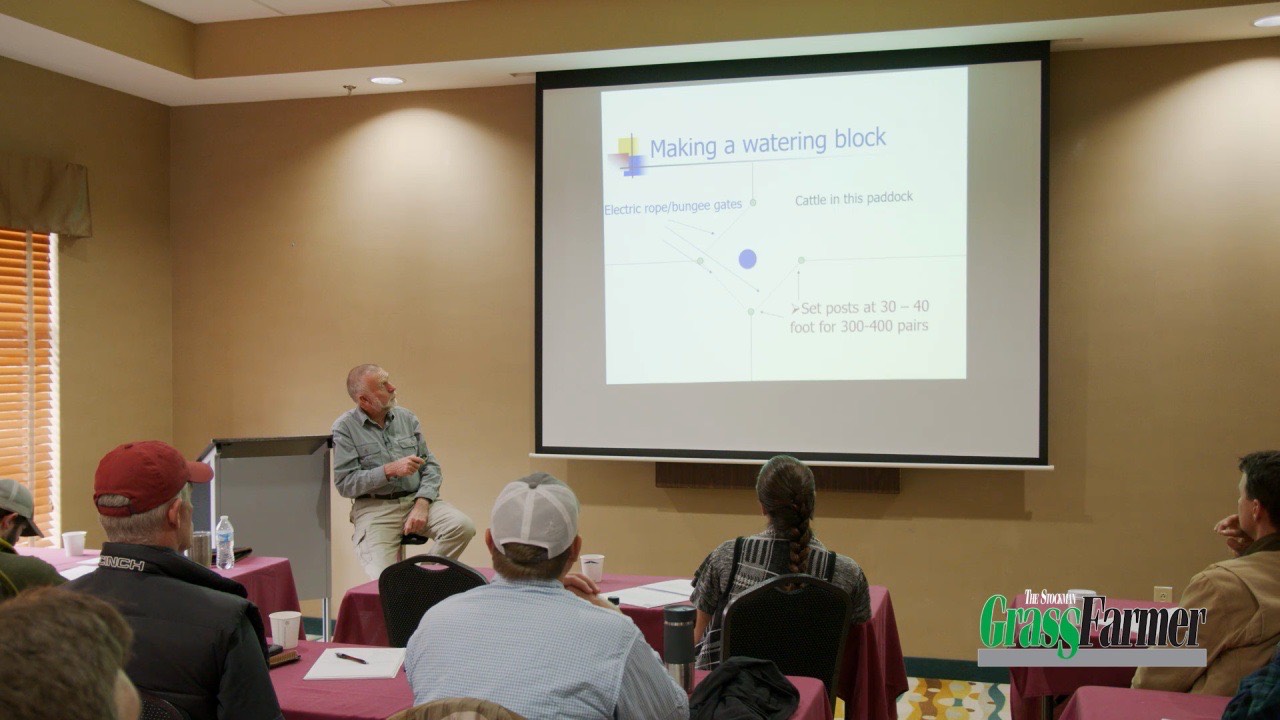

Yes, that means moving cows every day. It means installing water lines. It means looking at cow pies to see if they’re sheet cake, cookies, or pumpkin pie. It means looking at their left side to see how full it is. It probably means dismounting from your pickup truck and spending some time observing the herd. When everyone else is buying fertilizer, you’re installing electric fence webs all over creation. When everyone else spends half a day looking for cows during calving season, you can find yours in two minutes because they’re in a mob.

When neighbors say vaccination is the only way to avoid sickness, you buy kelp. When they’re buying cheap iodized salt, you’re getting the good stuff. And before you know it, you can have a thousand cows with no vet bills. Folks, that’s different.

- Patience. Allan’s axiom: “The biological clock runs on its own timetable; it can’t be hurried.”

He tried many ways to explain the difference between mechanical systems and biological systems. To be sure, he loved mechanical systems, especially if they pulled cars on a rail system (he loved steam engine trains). But he was often frustrated at people who assumed they could convert a landscape as quickly and efficiently as you can change paint on a house.

Routinely people want to know how fast they will see their worn out, weedy piece of land look like the fields enjoyed by long-time grass farmers. In general, it takes about three years for the soil to realize owners changed. And often, it gets worse before it gets better.

A common issue we deal with in our area is broom sedge. Under continuous grazing, poverty-soil indicator and unsightly broom sedge offers a drought-tolerant, late season succulence in August when pastures are shot and cows are desperate for something green to eat. It never expresses itself because it gets nipped off at a couple inches high. When our rest/exercise management starts, for the first time in decades the broom sedge can express itself. It grows tall, turns brown, and looks unsightly. Landlords complain.

But in a few years, with timely grazing management and some strategic shade mobile and mineral box placement, that broom sedge turns to orchardgrass, fescue, and clovers. Sure, you can buy a bunch of expensive amendments to try to hurry up the remediation, but nothing converts it overnight. Except maybe pastured poultry. That injection of impact plus poultry manure changes things faster than anything, but it still takes a couple of years to see a genuine sustaining transition.

How many words have been devoted to weeds in SGF? Thousands and thousands. Vegetation is a physical manifestation of whatev er management has gone before. Sometimes things have been improperly managed for decades when you come to a place. All of us old timers will tell you to do what you read about in these pages and the books from our library and in time you’ll see things change.

- Pennies. Allan’s axiom: “A cost eliminated is gone forever.”

He advocated value adding (and irritated a lot of old subscribers in the pro- cess) in the latter half of his life. The early years of SGF were all about becoming the least cost producer. bHe and Mississippi grazier Gordon Hazard teamed up to decry things that “rot, rust, and depreciate.” Allan coined the phrase “heavy metal disease.”

Gordon Hazard ran 3,000 stockers on his property with nothing more than a Chevy Luv pickup, a part-time local high schooler, and a 2,000 pound steer named Ug. He purchased land by selling off frontage lots and keeping 95 percent of the property inside that fringe. He had three rules for making money: buy and sell on the same day; keep every animal long enough to double its weight; keep everything at least a year. He was a shrewd penny-watch- er.

This pennies idea includes knowing other critical factors, like calving percentage, cow-days per acre, and depreciation. Too many farmers think the world owes us a living. We publicize the point by putting bumper stickers on our vehicles that say “No Farms, No Food.” It’s catchy and true, but a big difference exists between the aggregate and you as an individual. You’re competing with everyone and everything else in the food system with your cows, pigs, chickens, with your pastured livestock.

Do you time yourself on cattle moves? On gutting chickens? On handling sales? Toward the latter part of his life, Allan moved from least cost producer to craft producer, which is all about differentiation, branding, and direct marketing. In general, he said you could not cut expenses to wealth. At some point, you need to increase income, and that’s why in these pages we continually feature entrepreneurs who figure out how to capture retail dollars by wearing those notorious middleman hats.

If you know your property gives 65,000 cow-days per year, what would it look like if you put those through other things? Smaller cows? Stockers only? Cow-calf? Custom grazing? Boarding bulls for all the neighbors on a per-diem? Hot dogs in a concession stand?

Enthusiastic farmers have a handle on their pennies.

There you have it, the four big categories that differentiate between the farmers who are excited about the future and optimistic about opportunities versus those who are frustrated, depressed, and pessimistic. Notice not much of this is about breeding, forage varieties, or off-farm inputs. They’re about a mindset that liberates us to achieve our dreams.

As Allan would say, “Go for it.”

Joel Salatin is a full-time grass farmer in Swoope, Virginia, whose family owns Polyface Farm. Author and conference speaker, he promotes food and farming systems that heal the land while developing profitable farms. To contact him, email polyfacefarms@gmail.com or call Polyface Farm at 540-885-3590.

Stay connected with news and updates!

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from our team.

Don't worry, your information will not be shared.

We hate SPAM. We will never sell your information, for any reason.